On radical science as a subliminal political tool

People often say that “history is written by victors” but far fewer acknowledge that “history is written by the rich.” Written by those affluent enough to be literate, idle enough to read and debate, and with enough wealth to indulge the frivolous purchases of printed books. We know that the “scientific revolution”, the upheaval of thought, was only accessible to a few from the upper echelons of society yet we continue to hold onto the cherry picked stories of the patent office clerk who discovered relativity. Maybe because we are unaware, maybe because it gives us hope that insignificant life paths can still lead to greatness despite being bogged down by everyday worries.

And this sentiment is not new, for as long as there has been inequality, there have been people who have pushed against it. That is what this essay is about, an exploration of the significant class disparities, especially in the medical community, that stemmed from educational inequalities, and an examination of how various evolutionary theories emerged as a democratizing force within that context. We also discuss the content and implications of these issues, shedding light on the enduring impact of societal hierarchy on the development and dissemination of scientific knowledge.

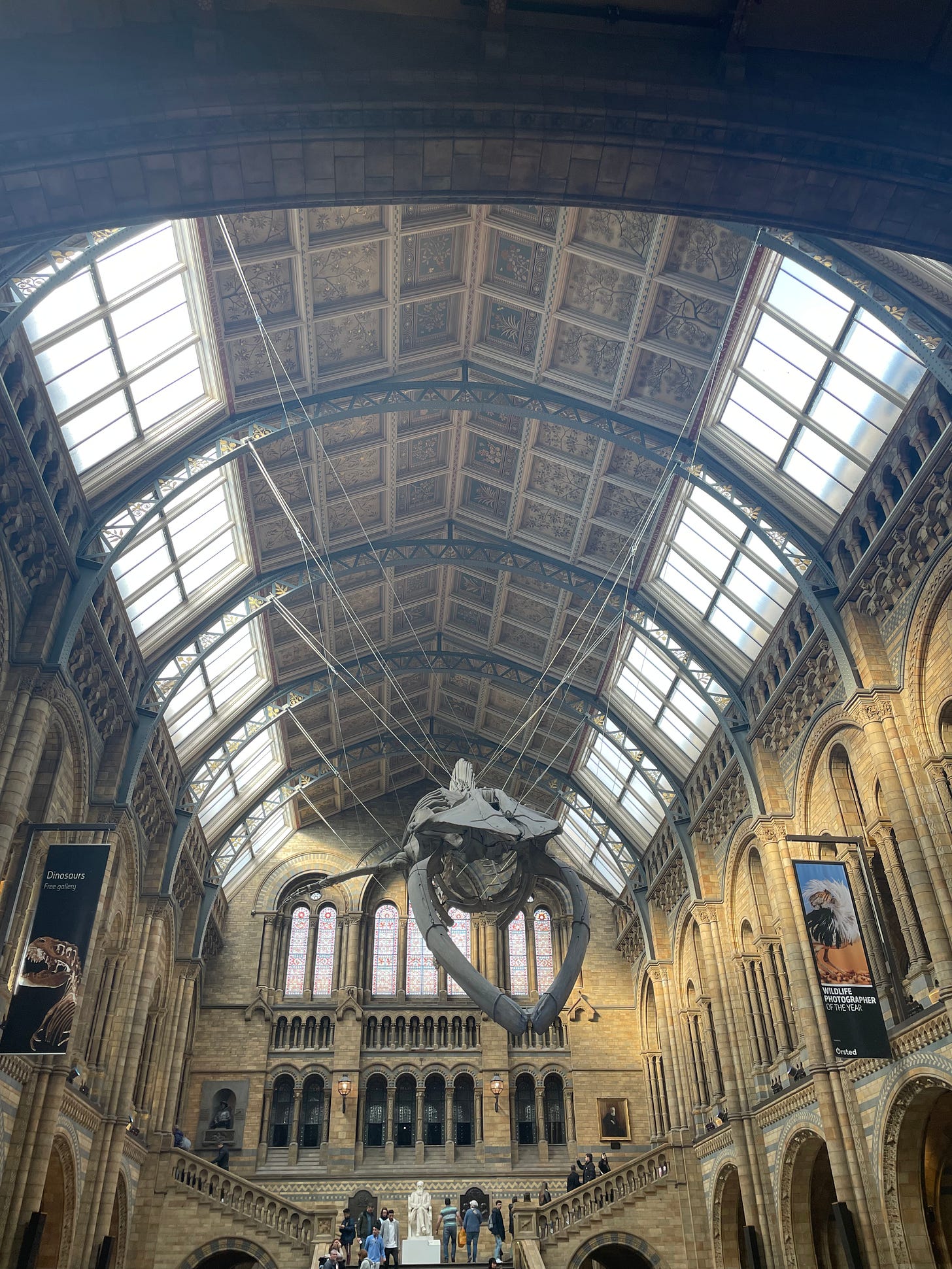

The tale follows the lives of rioting general practitioners, doctors without an education in the Classics from Oxbridge, who began putting down work on evolution long before Darwin entered the scene. However, the common pursuit of understanding human beginnings is where the similarities end. The medical schools of London resorted to illegal penny presses rather than distinguished arguments in libraries with ornate ceilings and they discussed evolution as a democratic force, a means against socio-economic subjugation, rather than a worthy pursuit in and of itself. Like Adrian Desmond put in his book, for the radical underworld “it [evolution] is about science to change society.”

These changes were taking place decades prior to the publication of “On the Origin of Species” however, no strong evidence for evolutionists from humbler means exists because the most prolific publishers of the time had nothing to gain from the theory’s widespread acceptance. Moreover, the more aristocratic rungs of society were still experiencing aftershocks from the French Revolution and feared that a democratic evolutionary theory would instigate a similar sentiment in Britain - giving them all the motivation they needed to sideline advances in the field from entering general scientific understanding.

This was in the 1830’s, a time where resources were scarce, and the Whig majoritarian government had just scrapped the old poor laws, making “survival of the fittest” a reality for a large percentage of citizens. No social welfare to fall back on created horrible labor conditions that furthered class division and shrunk the middle classes. It was amidst these conditions that the British radicals imported Lamarckism from their neighbors and historic rivals, France.

In a lot of ways this was the first condensed concept about human beginnings and revolves around a fairly simple main idea. Essentially, Lamarck maintained that animals could transcend into higher beings and pass on their characteristics without interference from a higher power. He also stated that the simplest form of life - “infusoria” - were spontaneously generated rather than created by God. This theory, printed side-by-side against the anti-aristocratic sentiment propagated in the penny presses meant that Lamarck’s theory, while academic in nature, very quickly became inextricably enmeshed with the cause of the working classes.

In hindsight, we can see why this might be a problem to the Church of England and those that drew on its wealth and stature for power. If living organisms had a “vitalist” agency that allowed them to be adaptive and progressive beings that, through some convoluted explanation, can evolve into higher organisms, then that makes all humans equal to one another. The clergy is not chosen by God and ruler’s don’t have a divine right to their power.

However, it was highly improbable that thinly veiled atheism would stand a chance in 1830’s Britain without any resistance which is where another possible explanation for evolution showed face. In his book “The Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation,” Robert Chambers presented the idea of development as lawful Creation, where God was not the maker but more a judge in court figure. This enlightened point of view was something that sat well with the middle classes, and more than the content of the theory, its mention earns its keep by bringing evolutionary science into the domestic sphere - imbuing the thought of human beginning into public consciousness.

While the general populace was slowly waking up to evolution, the big changes were happening within sidelined academic circles of London medical schools. Here the more philosophical study of comparative anatomy was taking off with general practitioners who were engaged in a torrid power struggle with the classically trained surgeons. One theory that is empirically evidenced and had a particularly strong hold on these institutions came from French zoology professor, Ettienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire who essentially stated that all vertebrate organisms are modifications of a singular form. Again this theory, which would later be spoken of in the same breath as Lamarckism, further went against the ethos of a divided society by putting humans at the same level as other “unintelligent” species.

Armed with this new found scientific basis for dissent, many previously marginalized groups lobbied for greater diversity in those who ran medicine. Positions in the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Surgeons were almost exclusively appointed based on nepotistic, discriminatory mandates that favored privilege over merit which did not sit well with the thousands of general practitioners brought together to strike – united by their common scientific interests and political woes. Yet, the aftermath of the strike was not as monumental as the practitioners hoped despite the intense push back from supporters of the Tory elite and things returned to business as usual with the exception of the foundation of modern day University College London – an institute that went on to become a hub for unconventional ideas and discourse.

However, as we have come to learn, neither the contemporary oligarchy nor the radical commoners were going to accept defeat without retaliation. Therefore when Geoffroy’s concepts of unitarism was experiencing a renaissance in Britain, so was his rival Cuvier’s opposing functionalist teleological approach that that drew on misinterpreted evidence against natural progressive evolution – the aristocracy were fast to jump in and claim it as their own contribution to the field. In essence, Cuvier believed in the idea of multiple creations, suggesting that new species were created after each catastrophic event to repopulate the Earth. This belief aligned with some theological idealists' views that God was responsible for the creation of species.

None of the many theories we have talked about really caught on with the wider scientific community but they did lay the groundwork for Darwin and his socially conservative approach that we still use as commonplace understanding. In many ways that may read like a failure in the modern context, but contemporary objectives were different. Studying evolution was never primarily about contributing to science. Even Darwin, who is considered to be so groundbreaking with his continuous but classification reliant ideas about development, refrained from publishing his book for twenty years – only letting out the scandalous pages of his notebook in death. Doing so while he was alive and telling his colleagues that organisms have unconscious but present agency in their progression would be catastrophic for his domestic life. He would have lost all the funding from his very rich father-in-law and betrayed the clerical order that he contemplated joining at one point. The fact remains that in Victorian Britain, talking about evolution was a deeply political act with far reaching consequences.

"There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone circling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved." - Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

While larger potential reforms got lost with the enticing prospects brought by the industrial revolution, we can see the remnants of the possibilities Victorian radicals spoke about within the medical community. The profession was highly stratified, with a clear distinction between the elite physicians who had been educated at Oxbridge and the general practitioners who did not. This educational divide was not just a matter of prestige, although a case was made for practitioner’s being unfit to treat the elite because their clientele also included the regular citizen, but also a matter of practical training. The elite physicians were trained in the Classics, which were seen as essential for understanding the philosophical body and better interacting with their more literate patients. These physicians and surgeons then went into the traditional apprenticeship system, which allowed them to learn from experienced physicians and to develop a network of professional contacts.

Evolutionary discourse opened up these silos and allowed the “less learned” practitioners to engage in intellectual debate, and draw from their more politically active counterparts in France and Scotland. Moreover, these new societies and hubs for debate were often open to anyone who was interested in science, regardless of their social background or education. Slowly the fiercely guarded lines between the niche of the medical profession broke down and new standards of rigor and academia were set in place to democratize and legitimize all kinds of doctors.

History may be written by the rich but as we see, the present is and the future can be written by everyone.

ReferencesConlin, Jonathan. Evolution and the Victorians: science, culture and politics in Darwin's Britain. A&C Black, 2014.

Desmond, Adrian J. The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in Radical London. The University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Gordon, Scott. "Darwin and political economy: the connection reconsidered." Journal of the History of Biology 22.3 (1989): 437-459.

Sloan, Phillip. “Evolutionary Thought before Darwin.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 17 June 2019, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/evolution-before-darwin/

Racine, Valerie. "Essay: The Cuvier-Geoffroy Debate." Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2013).

Originally published on Mundane Beauty, Spring 2023 (now archived)